Engaging Secondary Students in STEM Through Community Partnerships with ASAP

Building community partnerships into STEM projects have been shown to help increase access to STEM content for students and contribute to creating competent members of the STEM workforce.

Strong community relationships can also provide several benefits to teachers as well as the partners involved. However, localized partnerships can be difficult to achieve in a secondary school setting. The project discussed in this article attempts to show examples of the benefits that strong partnerships can provide to STEM students, teachers and the larger community. Students in an after school environmental club at Saguaro High School, in Scottsdale Arizona, worked with members of the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy and several other community groups to transform their high school campus into a “living laboratory”. Among other smaller projects, students and the partners removed invasive grasses from the campus grounds, replacing them with native pollinator plants, and established a controlled research plot on campus to investigate restoration techniques for saguaro cacti. Through the course of the partnerships and projects discussed, students had an opportunity to engage in relevant, real-world scientific research, build their STEM skills repertoire and learn the intricacies of experimental design while contributing to a larger community goal.

Introduction

In the next decade, job opportunities in the STEM work sector are projected to increase by nearly 11%, more than any other area (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2024). However, the increase in demand for STEM workers is quickly beginning to outpace the participation in, and the completion of STEM programs in secondary and post-secondary students, creating a gap in education that needs to be filled (De Meester et al., 2020). In many academic settings, students that begin in STEM fields often leave before they graduate, citing ineffective teaching strategies and lack of opportunity to build skills that adequately prepare them for potential careers (Hansen et al., 2021). This gradual loss of students, often referred to as the “leaky pipeline”, begs the need for real world STEM experience in schools and connection of content to students’ personal lives (Hansen et al., 2021; van den Hurk et al., 2019). However, it can be difficult to develop effective ways in the classroom to increase long-term student buy-in with STEM topics. Many districts, schools, and individual teachers have begun to adopt new pedagogical methodologies, such as project-based learning (PBL) and model-based inquiry (MBI), to try to make STEM subject matter more relevant (Hansen et al., 2021; Nation and Hansen, 2021). But these methods often don’t connect students with real-world opportunities that address local issues. Strengthening partnerships with STEM community members can provide a way to connect students with relevant skills, can benefit everyone involved and may be crucial to fostering long-term positive student attitudes toward STEM (Watters and Diezmann, 2013).

Benefits of STEM Partnerships

Often, the application of STEM principles can become irrelevant to students once they leave the classroom or complete a given course. But, by building connections with community partners to conduct more impactful projects, students can see the application of their skills in the real-world and build pathways toward potential STEM careers (Watters and Diezmann, 2013; Lopez et al., 2016; Tytler et al., 2018). When used alongside other methods, partnerships can boost student performance, interest, and retention in STEM fields and build leadership and civic engagement skills necessary for the workforce (Nation and Hansen, 2021; Karen et al., 2024; Watters and Diezmann, 2013). Through exposure to community-based science students suddenly become integrated into the needs of the larger STEM ecosystem and are positioned as agents of change early in their STEM careers. For students who may be unsure about their future in STEM, this can increase the relevancy of their skills and may help to lengthen retention times by providing an authentic context for what they are learning (Attard et al., 2021).

While localized STEM partnerships can enhance student engagement and performance across several domains, they can also be an effective way to build the pedagogical repertoires of teachers in the STEM disciplines and increase the retention rate of qualified teachers (Attard et al., 2021; Miller and Patel, 2016; Hutchison, 2012). Teachers, particularly at the K-12 level, while often excellent pedagogically, commonly do not have access to the training and support necessary to help provide STEM students with quality exposure to the content (Foster et al., 2010, Hansen et al., 2021). Professional development opportunities for teachers frequently seek to fill in these gaps, but teachers, especially at the secondary level, can sometimes be left with new ideas and not enough time or resources to effectively implement them. This is where engaging in community science by building partnerships for collaborative student projects can be a powerful way to achieve many things at once. By increasing teacher content knowledge, research skills and pedagogical design while simultaneously connecting schools to their community, these partnerships can help provide educators with the tools necessary to train, and retain, STEM students through their academic career (Miller and Patel, 2016; Allen et al., 2020; Nation and Hansen, 2021). In return, by building relationships with students and teachers, partnered scientists and community groups can enrich their outreach and research efforts, while helping to prepare the next generation of STEM workers (Nation and Hansen, 2021).

The Arizona STEM Ecosystem and the ASAP Program

Historically, Arizona has struggled to provide access to effective STEM learning for students at the secondary level (Hall, 2023). As a result, there is an increased need for effective resources and training for both teachers and students to reverse this trend. While community partnerships provide a method toward this, many educational institutions around Arizona are also beginning to offer better resources and opportunities for growth in areas of STEM instruction and student experiences. In particular, Arizona State University’s STEM Acceleration Project (ASAP), was recently developed specifically to provide Arizona K-12 educators with the funding, tools, and resources necessary to access STEM training for themselves and implement effective strategies in the classroom. ASAP teacher fellows received stipends for STEM materials and professional development to help them build a project at their school that engaged students in the use of STEM skills. Participating teachers were expected to document their projects and contribute four lesson plans to a database of open access lessons developed for instructors in the STEM disciplines. Between 2022-2024, this project accepted over 700 teacher fellows who participated in a total of 15,000 hours of professional development, engaged an excess of 180,000 Arizona K-12 students in STEM projects, and created a repository of over 2,000 field tested STEM lesson plans. These lessons and the resources created by the fellows can now be accessed by anyone on the ASU ASAP website.

I was an ASAP teacher fellow during these two years, while teaching biology at Saguaro High School. The resources provided by the ASAP fellowship were crucial in developing a localized partnership with the nearby conservation non-profit, The McDowell Sonoran Conservancy (MSC). Throughout the partnership, connections to other community entities including Scottsdale Community College (SCC), Northern Arizona University (NAU) and the Scottsdale Leadership Group were also made. The overall goal of these relationships was to engage students in real-world, relevant scientific research beyond the classroom to increase STEM content knowledge and skills. This article presents our project as an example of how community partnerships can provide students with authentic exposure to STEM, and can hopefully serve as a framework for other teachers to build similar projects.

Background and Overview of Partnership

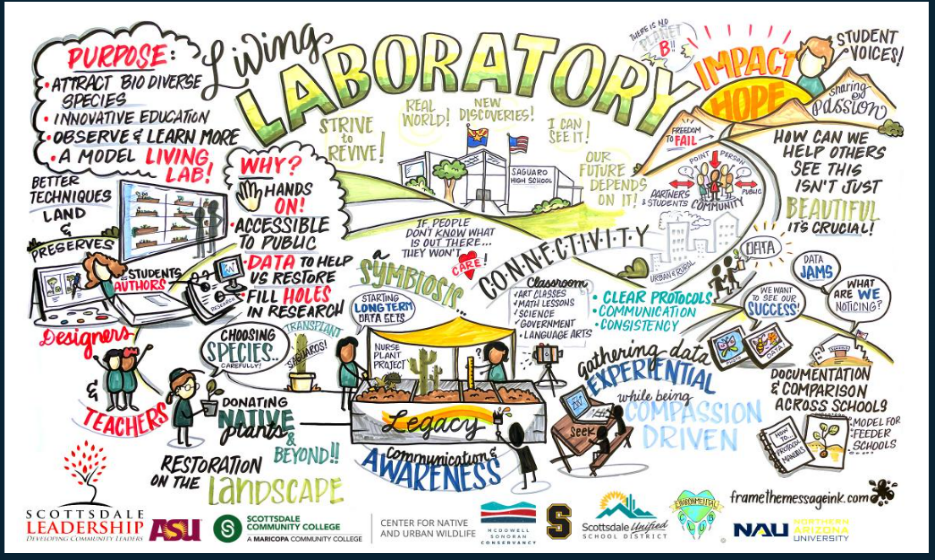

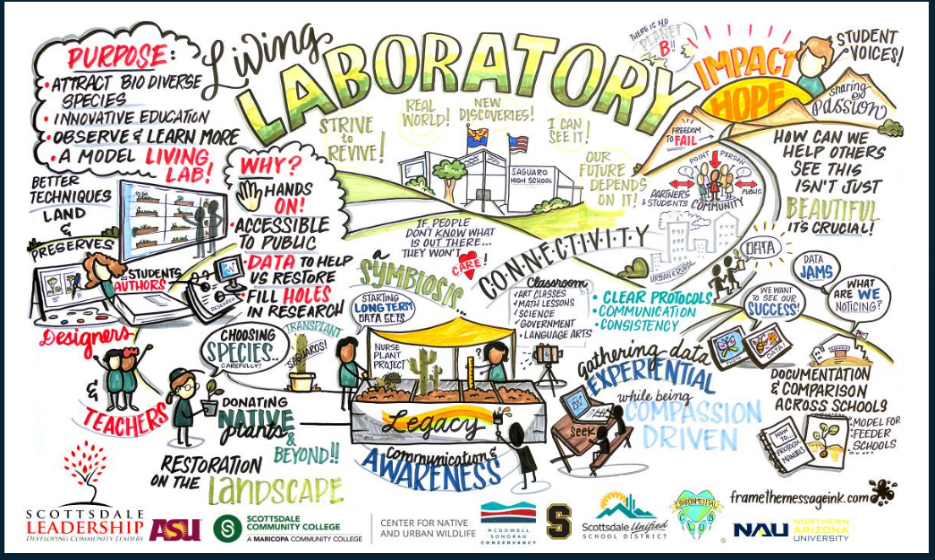

Saguaro High School is located in Scottsdale, Arizona a few minutes from SCC and not far from the McDowell Sonoran Preserve, a significant desert ecosystem located Northeast of Phoenix. Over the past few years, I have sponsored the Saguaro Environmental Club, a student-made, after school club, aimed at tackling issues of sustainability and environmental stewardship on campus and in the surrounding community. In 2022 our club, of about 25 active members, and the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy began building a partnership to develop a “living laboratory” on Saguaro’s campus. Our goal was to allow students to engage with the Sonoran landscape while providing teachers with a resource to incorporate local phenomena into their curriculum without leaving campus. Early on, students participated in a preliminary brainstorming session with the Conservancy and other community groups to help develop their “vision” and built a graphic roadmap as a representation of how they wanted to proceed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Living Laboratory Graphic Roadmap. Created by students and community members during our brainstorming session at the start of our partnership. The roadmap was animated live with the help of Frame the Message Ink and now hangs in the science building at Saguaro High School as a timeline and reminder to students.

Right away, students had a say in how they wanted to become involved, were able to communicate with industry experts and were poised as a critical part of the solution for the issues they identified. Students voiced interest in projects like learning about human-wildlife interactions, recycling and water conservation, tracking of Sonoran animal species, the impact of invasive species, the importance of native pollinators, and restoration techniques. By working with our partners to match the interests of students to the needs of the community and to the standards within the classrooms, the first two major components of the larger living labs vision began.

Creating the “Living Laboratory”

In our brainstorming session, students and partners identified two primary topics that they felt they could address on campus and would contribute to larger goals within the community: invasive plants and low biodiversity on our campus, and effective restoration techniques in the Sonoran Desert. To help form connections between their goals at school and the larger environmental implications, students were taken on a trip to the McDowell Sonoran Preserve where they had a chance to learn about similar projects in the field from Conservancy staff and stewards. Energized with ideas, students then developed a protocol for collecting biodiversity data at school before tackling the presence of invasive fountain grass (Pennisetum setaceum) and lack of pollinators on campus and altering their “lab” to explore the impacts. Club members divided the campus into eight relatively equally sized study regions and used iNaturalist and SEEK to gather preliminary biodiversity data. During their initial observations, students noted a lack of biodiversity on the school grounds and an obvious need for rethinking the landscape. Over the next several weeks, club members were involved in the process of working with multiple stakeholders to achieve a common goal and gained experience with the “behind the scenes” processes required for making change.

Students worked with SUSD facilities members to remove the invasive fountain grasses from campus, in particular from a large above ground planter, which would become their new pollinator garden. They then tilled and re-irrigated the planter, learning about plumbing, landscape design, irrigation and water conservation. In the following weeks, through the effort of many, the pollinator garden was planted with 15 different species of native plants all specifically included to attract pollinators in our area (See Figure 3). Shortly after, students collected more biodiversity data and began to identify a noticeable increase in species diversity on campus. Individual students and classes have since been using this pollinator garden for experiments and labs, such as teaching about photosynthesis and plant anatomy, that can be integrated into the curriculum of biology, chemistry, biotechnology, environmental science and other content areas with a little bit of creativity.

For the next component of the “living lab” partnership, students had a unique opportunity to help address a growing environmental issue, the impact of wildfires. In June 2023, the Diamond Fire degraded 2,000 acres of preserve landscape, quite literally clearing the slate for our next major project to begin. Though students had already planned to explore components of restoration ecology as part of their goals, the fire was a stark example of the need for effective restoration strategies. It also was a perfect example of the benefits that can come from building community partnerships, giving students a chance to engage in a meaningful project while also supporting a larger community goal. Through mentorships from NAU’s Dr. Helen Rowe and the MSC, students began to explore the impacts of disturbances like a fire and methods for ecosystem recovery afterward. In particular, students learned about Saguaro cacti (Carnegiea gigantea), their role in the ecosystem, and efforts for their conservation and restoration.

The Saguaro cactus, though enigmatic in the Sonoran Desert, is threatened by rising temperatures, increased occurrence of wildfires and illegal poaching among other things (Hultine et al., 2023). However, as an important keystone species, Saguaros provide shelter, nutrients, water and energy to many desert consumers while helping to support a diverse group of pollinators and are crucial plants to consider when discussing desert restoration (Winterbottom, 2021). Despite their importance, it is not well understood what conditions are optimal for their re-establishment after a major disturbance. So, as a component of a larger project being conducted by Dr. Rowe and the MSC, students began to investigate the potential benefits of various nurse conditions on the early establishment of Saguaro pups. Plant nurses, as they learned, can come in a variety of forms, and are generally thought to provide beneficial environmental conditions to help support growth in harsh desert environments (Drezner and Garritty, 2003). Commonly, cacti are observed growing near larger plants, or rocks, potentially providing seedlings with protection from predators, shade, and a nutrient island to spur initial growth. Studies evaluating the impact that nurse conditions like this can have on Saguaro pups have suggested that the establishment and survival rate of Saguaros increases significantly in the presence of nurse plants and rocks (Valientebanuet and Ezcurra, 1991; Drezner and Garritty, 2003). However, relatively few studies have been conducted in a controlled setting where nurse conditions are intentionally manipulated to investigate their impact. Therefore, our new partnerships and available space on campus provided a perfect opportunity for the Environmental Club students to conduct a practical and important experiment. Students tilled and re-irrigated another planter on campus through several weekends of work and much help from our partners once again. They then measured 40 evenly sized research plots (1.2m X 1m) and planted a Saguaro pup aged just a few months in the center of each plot. Each of these plots then had randomized nurse condition treatments included with the cactus; incorporating either a nurse rock, a nurse plant, shade cloth, or combinations of these conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A graphic representation of our completed Saguaro-nurse condition planter. Plots that are shaded in darker received 50% shade cloth on their Southeast side as part of their treatment, uniform sized paving stones were used as nurse rocks and the Triangle Leaf Bursage (Ambrosia deltoidea) was used as a nurse plant.

Once our planter was completed, students and our partners began collecting baseline data on cactus height, rib count, areole count, and width (See Figure 3). Right away, students got a first-hand look at the intricacies of data collection as new field biologists. Over the next several months, students continued to monitor growth trends in the cacti, working through inconsistencies in data collection methods and modifying them as a real scientist would to develop an effective protocol. Since the larger goal of this planter was to imply restoration strategies for cacti that were burned on the Preserve, students also had a chance to put their new skills into action out in the field. After installing our planter, we took another field trip to the Preserve to assist with planting sister study plots spread across the Diamond Fire burn scar. Since the establishment of the study areas, students have participated in several rounds of data collection, which is still ongoing, and have begun to note trends in the effect of the nurse conditions on cacti growth. These data will be used by the MSC, NAU researchers, and other ecologists to better understand methods for the re-establishment of saguaros after disturbances in the desert and will provide continued opportunities for students on Saguaro High School’s campus to participate in research that has a real impact.

Figure 3: Left-A few of the Environmental Club students planting native pollinator species in their newly cleared pollinator garden. Right-A student collection height data on one of the newly planted Saguaro pups.

Project Outcomes

This partnership was a pilot to determine the feasibility of developing something like this at the high school level and hopefully provide a template for other schools. Many of the components and projects discussed in this article are ongoing. Given the new partnerships formed and the experimental nature of the projects, the initial stages involved a relatively small number of students that volunteered many hours of after school time over the past two years. It quickly became clear that is not an easy ask and can be a huge lift for students, teachers, and partners to support. However, with enough effort, the benefits for those involved are significant. The core group of students had opportunities to interact with career scientists outside of a classroom setting, they learned the “behind-the-scenes” efforts needed to complete a complex scientific project and they made connections to careers and community members involved in important areas of STEM work. Most impressively, a small group of students had an opportunity to present the story of their project at the MSC’s Parsons Field Institute Science Symposium at the end of 2023 and authored a journal article about their experiences, titled “Saving Saguaro Cacti at Saguaro High School”, which was published in the Cactus and Succulent Journal in May 2024. For the students involved, these experiences are priceless opportunities for them to communicate scientifically and engage with career scientists in a legitimate way while exposing them to STEM beyond the classroom. Overall, through the course of this project, four things happened that I believe are vital to strengthening the STEM experience for students and benefiting the STEM ecosystem.

- Students received in-depth training and exposure to real science and put the training into practice to address real issues

- As the teacher and club sponsor, I gained valuable professional development and research training that enhanced my ability to teach science skills and help students apply them to real-world issues.

- Community partners engaged with the next generation of scientists, positioning them as change agents and developing projects with broader implications for science and local restoration efforts.

- Saguaro High School created a space that teachers and students can use to enhance course material or explore their local ecosystem without leaving campus.

Remaining Needs

Given that large-scale community science is relatively rare in secondary schools, there are many remaining needs. It can be difficult to ask teachers, students, and community members to dedicate multiple hours of time each week to work outside of the classroom, however this can be what is required for building strong community connections. Therefore, external supports, extra resources, and potentially extra incentives for teachers and students may be necessary to help increase the amount of those willing to explore projects like this. I was very lucky to have had a supportive administration and district, and received ample external supports from the ASAP program and the partners involved. However, this may not be available to all teachers and other avenues should be explored to help supplement areas where there may be a gap in resource availability.

Acknowledgements

No part of this project would have been possible without the support of the following groups and people: ASU’s ASAP fellowship program, Scottsdale Unified School District, Johanna Kaiser, SUSD facilities lead Joe Arteca, and Saguaro High School, Dr. Helen Rowe from Northern Arizona University, Scottsdale Community College and Natalie Case of the Center for Native and Urban Wildlife, the Scottsdale Leadership Group and Frame the Message Ink, and of course the students who are a part of the Saguaro Environmental Club. I would like to especially thank The McDowell Sonoran Conservancy staff and stewards for dedicating countless hours to helping with this project. All of the mentioned groups were intricately involved in the building of the partnerships and projects discussed in this article.

Note: Interested readers can access a GIS Storymap made by students at the end of the first year of our partnerships with more information about their projects at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/debd3cadabc24201a49c6266ffe54e49

Authored by Scott Milne

References

Allen, P. J., Lewis-Warner, K., & Noam, G. G. (2020). Partnerships to Transform STEM Learning: A Case Study of a STEM Learning Ecosystem. Afterschool Matters, 31, 30-41.

Attard, C., Berger, N., & Mackenzie, E. (2021, August). The positive influence of inquiry-based learning teacher professional learning and industry partnerships on student engagement with STEM. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 6, p. 693221). Frontiers Media SA.

De Meester, J., Boeve-de Pauw, J., Buyse, M. P., Ceuppens, S., De Cock, M., De Loof, H., ... & Dehaene, W. (2020). Bridging the Gap between Secondary and Higher STEM Education–the Case of STEM@ school. European Review, 28(S1), S135-S157.

Drezner, T. D., and C. M. Garrity. 2003. Saguaro distribution under nurse plants in Arizona's Sonoran Desert: directional and microclimate influences. The Professional Geographer, 55(4), 505–512.

Foster, K. M., Bergin, K. B., McKenna, A. F., Millard, D. L., Perez, L. C., Prival, J. T., ... & Hamos, J. E. (2010). Partnerships for STEM education. Science, 329(5994), 906-907.

Hall, C. J. (2023). The STEM Teacher Shortage: A Case Study Exploring Arizona Teachers' Job Satisfaction and Retention Intention (Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University).

Hansen, A. K., Connors, P., Donnelly-Hermosillo, D., Full, R., Hove, A., Lanier, H., ... & Zavaleta, E. (2021). Biology beyond the classroom: Experiential learning through authentic research, design, and community engagement. Integrative and comparative biology, 61(3), 926-933.

Hultine, K. R., T. Hernández-Hernández, D. G. Williams, S. E. Albeke, et al. 2023. Global change impacts on cacti (Cactaceae): current threats, challenges and conservation solutions. Annals of Botany, 132(4), 671–683.

Hutchison, L. F. (2012). Addressing the STEM teacher shortage in American schools: Ways to recruit and retain effective STEM teachers. Action in Teacher Education, 34(5-6), 541-550.

Karen, K. A., Snyder, B. A., & Adams, R. (2024). Investigating a Role for Model-Based Inquiry in an Undergraduate Introductory Biology Lab. The American Biology Teacher, 86(6), 352-360.

Lopez, C. A., Rocha, J., Chapman, M., Rocha, K., Wallace, S., Baum, S., ... & Mothé, B. R. (2016). Strengthening STEM education through community partnerships. Science education & civic engagement: an international journal, 8(2), 20.

Miller, S., & Patel, C. (2016). Fostering K-12 teacher engagement in STEM through partnerships. In ICERI2016 Proceedings (pp. 7155-7163). IATED.

Nation, J. M., & Hansen, A. K. (2021). Perspectives on community STEM: learning from partnerships between scientists, researchers, and youth. Integrative and comparative biology, 61(3), 1055-1065.

Tytler, R., Symington, D., Williams, G., & White, P. (2018). Enlivening stem education through school-community partnerships. Stem education in the junior secondary: The state of play, 249-272.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). STEM employment. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/stem-employment.htm

Valiente-Banuet, A., and E. Ezcurra. 1991. Shade as a cause of the association between the cactus Neobuxbaumia tetetzo and the nurse plant Mimosa luisana in the Tehuacan Valley, Mexico. The Journal of Ecology, 961–971.

van den Hurk, A., Meelissen, M., & van Langen, A. (2019). Interventions in education to prevent STEM pipeline leakage. International Journal of Science Education, 41(2), 150-164.

Watters, J., & Diezmann, C. (2013). Community partnerships for fostering student interest and engagement in STEM. Journal of STEM education, 14(2), 47-55.

Winterbottom, C. A. 2021. The Efficacy of Saguaro Cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) Pollination Systems (Doctoral dissertation, Northern Arizona University).

Related Content